The Melville Douglas Global Equity fund is domiciled in Jersey. Although this small island is within sight of the northern French coastline, it has been ruled by an English monarch ever since William the Conqueror grabbed the throne in 1066. Over the centuries the French have tried and failed to pluck this little thorn in its side. Their key hindrance was the sea. This natural moat is a treacherous mix of perilous currents and thousands of submerged rocks.

Just as a physical moat has defended Jersey over the centuries, a company can protect profits by building an “economic” moat, or competitive advantage. A basic tenet of microeconomics is that a company earning high returns will attract competitors who also want a piece of the action. Most of the time companies with narrow or non[1]existent moats will not be able to stop new entrants from taking market share and cutting prices. This dynamic turns a high returning business into a mediocre one. However, there are a very small minority of businesses that defy competitive gravity and enjoy many years of high profits and shareholder wealth creation. These wide economic moat companies are core holdings in the fund.

What can provide moats?

There are many ways in which a company can gain a competitive edge. A low-cost open cast mine with high grade deposits may have a cost advantage. A pharmaceutical company will have patent protection. However, mining depletes finite resources and drug patents typically expire after a decade of commercial sales. To stand still, let alone grow, another huge deposit or blockbuster drug must be discovered. We find more sustainable moats can be built around value-adding brands, network effect and high switching costs.

Moat-creating brands cannot just be well known, they must add perceived value. A great example is the cosmetics industry. Estee Lauder can charge massive margins on its premium skincare products as its customers find it more difficult to trade down a perceived notch on their beauty rather than, say, on a tin of baked beans.

Brands also add value if they lower search costs, i.e. the time spent shopping around. For example, many people buy online through Amazon without checking prices elsewhere. This is because trust is even more important online than offline. When buying on the internet you need to hope that you receive what is ordered, your credit card is not compromised, and the seller will take the product back and provide a refund. Amazon’s brand has built a second to none moat from this perspective.

A network effect can be very powerful. This is where the service increases in value as the number of users expand. Think of Visa and Mastercard. Each additional cardholder on their network makes their brand more attractive for businesses to accept Visa or Mastercard payments. While each new business that accepts Visa or Mastercard makes the brand more attractive to cardholders. A new competitor network would be prohibitively uneconomic to set up today as it would take many billions of US dollars and decades of intermediary relationships and brand building to replicate.

High switching costs are also a great source of competitive advantage. An example is a Linde-installed and managed industrial gas facility at an oil refinery or blast furnace. There is no benefit to the customer from incurring the huge disruption costs of halting production as a result of ripping out and replacing an embedded part of their process.

It is also important to recognise what does not provide a moat. Having the latest hot gadget or high market share is not a moat. For example, Nokia had 50% market share of smartphones in 2007 but it failed to catch the next big wave. Nor should it be dependent on management skill. Peter Lynch, the legendary fund manager of Fidelity’s flagship Magellan global equity fund, once quipped that investors should buy a business that is so good that an idiot can run it, because sooner or later an idiot will run it.

How do you know whether a moat is effective?

Moats generally manifest themselves in pricing power. Once a company loses the ability to raise prices then it is often an early signal of an eroding moat.

To quote Warren Buffet, “The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price 10%, then you’ve got a terrible business”.

Are wide moats already reflected in the share price?

Surprisingly, often not.

In our day-to-day lives we are prepared to pay up for quality as we know being frugal does not just mean spending less money. It is worth paying a little bit more for a reliable car or for competent legal, medical and financial advice.

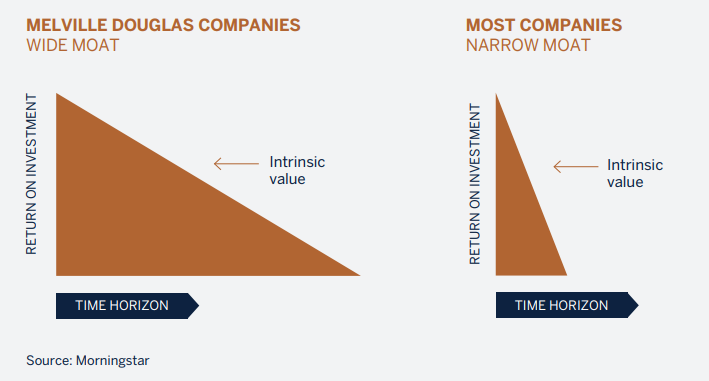

But in the investment world economic moats are often not fully priced into share prices. This is because a high component of stock market trading is made up of short-term investors who place more weight on the here[1]and-now. Will a company beat earnings expectations next quarter? How long will the recession last? By doing so they end up underestimating the enormous magnifying power of compound returns over the years and decades derived from wide moat businesses.

This time-horizon induced anomaly provides a repeatable and lucrative opportunity for long term investors. A wide moat compounder is a forgiving stock to own even if an investor pays a full price at the outset. As illustrated in the chart, so long as you are a patient holder through the ups[1]and-downs of business cycles the intrinsic value per share will eventually grow above the initial price paid.

Adapt or stagnate

The final point is that an investor cannot simply buy and forget. Moats can quickly dry

up. Competitive advantages are rarely permanent, particularly amidst a fast-changing

competitive landscape. The next Airbnb, Uber or Amazon will always be around the

corner to upend the status quo. As such we have a healthy sense of paranoia that

today’s winner might be tomorrow’s value trap. Testing the strength of a company’s

defences is an ongoing task. The saving grace is that although the names may change

in the fund, we are clear about what we want to own.